Paragangliomas are rare, highly vascular neuroendocrine tumours derived from the autonomic nerve ganglia. They are classified according to the anatomic location and hormonal activity. Cardiac paragangliomas are the rarest primary cardiac tumours and account for less than 1 % of cases.1 The presentation is varied depending on the location of the tumour, secretory/non-secretory type or causing obstruction.

Case Report

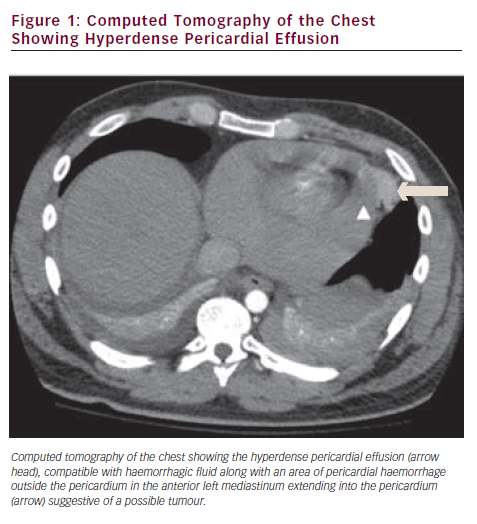

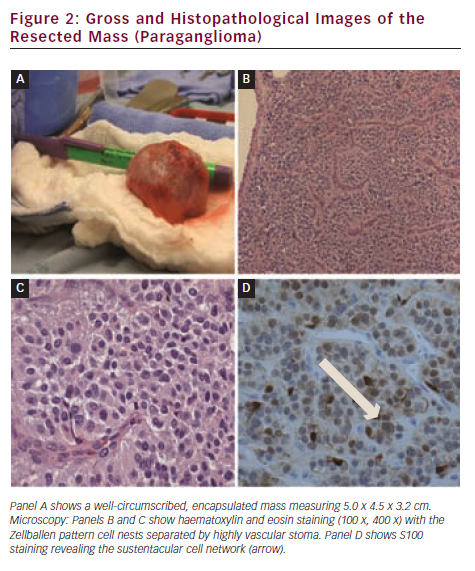

A 24-year-old Caucasian man without any significant past medical history presented to the emergency department with complaints of sudden onset of chest pain and shortness of breath. Pain was located at the left sternal border, sharp in character, 5/10 in intensity (on a scale of 1–10) worsening with deep breathing and without any radiation. The pain started suddenly when he was skiing halfway down the slope and went into a tuck position. Physical examination revealed a temperature of 99.6 °F, a heart rate of 136 beats/min, a respiratory rate of 28 breaths/min, and blood pressure of 90/60 mmHg. Cardiovascular examination was significant for pale conjunctiva, elevated jugular venous distension, tachycardia and audible two-component friction rub. His electrocardiogram (ECG) revealed sinus tachycardia with diffuse ST-T elevation and PR depression suggestive of acute pericarditis. Cardiac biomarkers and chest radiograph were within normal limits. A transthoracic echocardiogram revealed moderate pericardial effusion with tamponade physiology. He underwent emergent percutaneous fluoroscopic guided pericardiocentesis with recovery of 200 cc of blood, and then was transferred to the intensive care unit for close monitoring. A few hours later he became tachycardic and hypotensive. A stat echocardiogram revealed re-accumulation of pericardial fluid. He underwent a second fluoroscopic-guided pericardiocentesis with removal of 300 cc of blood. Within minutes the pericardial fluid re-accumulated and the patient became tachycardic. A computed tomography scan of the chest was immediately done to rule out other causes of the effusion. It revealed the pericardial effusion, and haemorrhage in the anterior left mediastinum with pericardial extension (see Figure 1). A cardiothoracic surgeon was consulted and they proceeded to explore the pericardial sac. During the surgery 300 cc of unclotted and clotted blood was removed from the pericardial sac. Further exploration revealed a bluish coloured structure communicating with the pericardium, adjacent to the ascending aorta and the superior vena cava and extended from the base of the heart going towards the right brachiocephalic artery. The 5.0 x 4.5 x 3.2 cm mass was excised under protection of cardiopulmonary bypass. The mass was diagnosed histo-pathologically as paraganglioma (see Figure 2, Panels A, B and C) with the characteristic packed appearance (in German ‘Zellballen’ pattern). Immunohistochemical studies were positive for chromogranin, cluster of differentiation (CD) 57 and synaptophysin. Staining for S-100 protein was positive for the sustentacular cells, which supported the diagnosis (Figure 2, Panel D). Pericardial fluid analysis did not reveal any malignant cells. Post-operative serum metanephrine and normetanephrine levels were within normal limits. The patient had an uneventful recovery and was discharged home on day five post-operatively.

Discussion

Paragangliomas are rare non-chromaffin tumours that grow from neural crest cells. They are slow growing tumours and arise from extra-adrenal autonomic ganglia in the head, neck, mediastinum, heart, retroperitoneum and pelvis. These sympathetic paragangliomas, if hormonally active, are often described as extra-adrenal pheochromocytomas. Germline mutations of the succinate dehydrogenase subunit B, C, D and other mutations have been associated with familial pheochromocytoma-paraganglioma syndrome.1

Cardiac paragangliomas constitute less than 1 % of primary cardiac tumours,2 which may be benign or malignant. They can also be hormonally active or inactive. These tumours can arise either from branchiomeric paraganglia or visceral autonomic paraganglia.3 In this case we think that it was arising from the sympathetic fibres of the heart and was inactive. Hormonally active tumours primarily produce norepinephrine, normetanephrine and symptoms to those produced by a pheochromocytoma including episodic headache, sweating and tachycardia. Inactive tumours are more common in the pericardium and can present in a variety of ways.4 Cases have been reported of patients presenting with symptoms of angina, shortness of breath and symptoms similar to acute pericarditis. These symptoms are usually due to cardiac compression or even tamponade. In our case, the patient presented with sudden onset of chest pain and shortness of breath secondary to pericardial tamponade. These tumours are highly vascular tumours. In our patient, we hypothesize that while skiing he might have performed significant valsalva that ruptured the mass involving the pericardium leading to the pericardial tamponade.

Cardiac paragangliomas are diagnosed with non-invasive imaging including echocardiography, computed tomography (CT), magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), and MIBG (iodine-131-meta iodobenzylguanidine) scanning.5,6 Surgical resection with or without embolisation is the treatment of choice. Transplantation has been utilised as a therapeutic modality in cases where paragangliomas invade atrioventricular groove, direct coronary artery involvement or extend into the left ventricle.3 Surgery is curative if the mass is removed in its entirety. It can be a complex surgery depending on the size and location of the tumour. These tumours parasitise the cardiac blood supply making them very difficult to resect or excise. Prior to the surgery we should be aware of whether the tumour is hormonally active or not to avoid potential complication associated with anaesthesia and blood pressure control. In this case we proceeded to the surgical removal of the tumour due to acuity and unawareness of the tumour diagnosis. In retrospect, we think that for non-emergent surgery, patients should have baseline assessment for urine and serum metanephrines, after a diagnosis of cardiac or extra cardiac tumour. Due to the genetic association of paragangliomas tumours his family was referred for genetic counselling.

Conclusion

This case is an unusual presentation of a cardiac tumour with chest pain and good surgical outcome. In all cardiac or extra cardiac tumours we should pre-operatively check for hormonal activity and pre-operative and intra-operative adrenergic blockade must be employed in all secretory paragangliomas.